The Gates of the Great Continent: Palestine, China, and the War for Humanity’s Future

As Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza enters its sixth month, Qiao Collective presents an urgent intervention from Charles Xu on the Palestinian resistance and the place of China, its people, and their revolutionary legacy in the global solidarity movement.

This essay details China’s near-unconditional support for Palestinian armed struggle in its early phase, and the enduring bonds forged between both peoples even through the Oslo Accords and the resistance’s turn toward political Islam. It then analyzes the balance of forces since October 7 through the lens of Mao’s writings on guerrilla war, and also draws parallels between the mutually-reinforcing sovereign technological projects of China and the Axis of Resistance. Through the interlocking stories of former Red Guard Zhang Chengzhi and the Japanese Red Army, it argues that Palestine must be the fulcrum for any pan-Asian liberation struggle.

Table of Contents

Part I: Palestine and China at the High Tide of National Liberation arrow_upward

Imperialism is afraid of China and of the Arabs. Israel and Formosa are bases of imperialism in Asia. You are the gate of the great continent and we are the rear. They created Israel for you, and Formosa for us. Their goal is the same.

— Mao Zedong to visiting Palestine Liberation Organization delegates, Beijing, 1965

Imperialism has laid its body over the world, the head in Eastern Asia, the heart in the Middle East, its arteries reaching Africa and Latin America. Wherever you strike it, you damage it, and you serve the World Revolution.

— Ghassan Kanafani, quoted in The 1936-39 Revolt in Palestine (1972)

Between these two striking images of imperialism – drawn by perhaps the most iconic Chinese and Palestinian revolutionaries of the twentieth century, both literary giants in their own right – we can discern a common thread. Mao and Kanafani each envisioned their enemy as an active, intentional, even organic force, concentrating its energies on the eastern and western extremes of Asia. Both identified Israel as the “heart” of the Empire, its battering ram against the “gate” of the Orient. The corollary to their insight is that Palestine’s century-long struggle against Zionist colonialism is the fulcrum of pan-Asian revolution, and its liberation would be an event of equal if not greater world-historic importance than China’s own.

In their respective national historiographies the State of Israel and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) were born just one year apart, in 1948 and 1949 respectively. Legally speaking the former was midwifed by both sides of the nascent Cold War with United Nations blessing; in actual fact it was born in blood, through the originary genocide of the Palestinian Nakba. The latter emerged through equally violent struggle against the colonial yoke, and within a year would find itself at war with imperialist armies flying that same UN banner. From today’s vantage point it is a fact rich with historical irony that at the time, much of the global left viewed both developments as historically progressive.

In those early years China itself was by no means free of such analytical limitations when it came to Zionism and the Palestinian national question, as Johns Hopkins scholar Zhang Sheng points out. Though never as effusive about Israel’s potential as the Soviets initially were, PRC leaders at first broadly shared their view that it was “a progressive, left-leaning state that could potentially become an ally in the struggle against Western hegemony.” Zhang notes that deeply contradictory positions could be found within the same officially-sanctioned publications. For instance, The Truth of the Palestinian Issue (1950) condemned Zionism as the “vanguard of the imperialist conspiracy to enslave Palestine,” while simultaneously decrying the “aggressive invasion” of Israel by Arab monarchies helmed by Jordan, a “running dog of British imperialism.”

For its part, Israel unilaterally extended diplomatic recognition to the PRC as early as 1950, well before any other country in the Middle East. The People’s Daily, official organ of the Communist Party of China (CPC), welcomed this gesture but state leaders wisely opted not to reciprocate. Unofficial relations would almost immediately sour over Israel’s backing for the US-led intervention in the Korean War. They would further deteriorate as China made diplomatic and cultural overtures to Arab and other Islamic countries, in a process often mediated by Hui and Uyghur dignitaries who advanced a vision of pan-Islamic resistance to Western imperialism. By the time of the 1955 Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, hosted by the fiercely anti-Zionist Indonesian leader Sukarno, China was unequivocally backing the right of return for Palestinian refugees.

Shortly thereafter came the joint Israeli, British, and French invasion of Nasser’s Egypt in October 1956, just months after the latter had become the first Arab country to establish relations with the PRC. Iraq would follow suit in 1958 when the 14 July Revolution overthrew the Hashemite monarchy; almost simultaneously, US Marines invaded Lebanon to violently put down a revolutionary challenge to its comprador regime. Amid these clarifying developments, China came increasingly to envision itself as a “home front of the Arab people’s struggle against imperialism” and to mobilize its people accordingly, as noted by Fudan University historian Yin Zhiguang. The battle lines were at last being firmly drawn, just in time for the Palestinian national movement to erupt emphatically onto the world-historical stage.

This new phase of struggle began in 1964 with the founding of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as a political organ not subordinate to any other Arab state. A year later China became the first non-Arab country to extend formal diplomatic recognition to the PLO, which moved quickly to open an embassy in Beijing. Its support for the Palestinian armed struggle extended well beyond the rhetorical: Lillian Craig Harris notes that “between 1964 and 1970 the Palestinians fought with Chinese-made weapons, implying that the PRC was [their] exclusive supplier among the big powers.” This aid reportedly included AK-47s and other Soviet-model light arms, anti-tank artillery, US-model rocket launchers, and radio equipment, predominantly delivered through Syria and Jordan. Starting in 1967, the PLO also sent multiple contingents of a dozen or so fighters each (mostly drawn from the leading faction Fatah) to China for months-long training regimens in the theory and practice of guerrilla warfare.

Across factional divides, Palestinian revolutionaries were almost unanimously effusive in their gratitude for China’s moral and material solidarity. Ahmed Shuqairy, the first chairman of the PLO, went so far as to claim that “Palestinians should feel grateful not to other Arabs but to the gallant and generous Chinese people, who helped our revolution movement long before the Arab heads recognized the PLO. It is not, as some seem to think, propped up by Nasser or any other Arab leader." His successor Yasser Arafat, who would visit China fourteen times during his 35 years at the helm of the movement, credited the PRC as “the biggest influence in supporting our revolution and strengthening its perseverance.” George Habash, founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), insisted that “our best friend is China. China wants Israel erased from the map because as long as Israel exists, there will remain an aggressive imperialist outpost on Arab soil.”

Palestine solidarity demonstration in Beijing, 1969. The banner reads “Resolutely support the struggle of the Palestinian and Arab peoples against Zionism and US imperialism!”

China’s affinity for the cause of Palestinian liberation in fact had deeper roots than this simple convergence of strategic interests. As Harris points out, “despite great differences, the Palestinian arena is the Arab world situation which comes closest to fitting the Chinese experience of revolution against an imperialist invader.” Allusions to the 1937-45 War of Resistance against Japan, which elevated the CPC’s capacity for “protracted people’s war” to new heights, abounded in Chinese statements of solidarity with Palestinian guerrillas. In Mao’s aforementioned 1965 address to visiting PLO delegates, for example, he mused that

You are not only two million Palestinians facing Israel, but one hundred million Arabs. You must act and think along this basis. When you discuss Israel, keep the map of the entire Arab world before your eyes … peoples must not be afraid if their numbers are reduced in liberation wars, for they shall have peaceful times during which they may multiply. China lost twenty million people in the struggle for liberation.

Chinese leaders also took their historical cues from the anti-Japanese struggle, where the Communists formed a United Front with their bitter ideological enemies in the Kuomintang, when judging how to allocate support between different factions of the PLO. Far more than strict theoretical alignment they prioritized political and military unity, displaying a marked preference for Fatah’s cross-class nationalism over the avowedly Marxist-Leninist PFLP (particularly during the latter’s campaign of airline hijackings). In his 1965 speech, for instance, Mao cautioned his audience: “Do not tell me that you have read this or that opinion in my books. You have your war, and we have ours. You must make the principles and ideology on which your war stands. Books obstruct the view if piled up in front of the eye.” And during another visit in 1971, premier Zhou Enlai recommended “that Palestinian organizations merge in one genuine unity that will have only two organs: one for leading the armed struggle, and the other political, and that the PLO will become the main nucleus of the Palestinian people.”

Throughout this period, China’s rhetorical militancy in defense of the Palestinian armed struggle – and to some extent the volume of its material support – also admittedly waxed and waned in accordance with political exigencies. It peaked in the aftermath of Israel’s disastrous defeat of multiple Arab armies and subsequent occupation of Gaza, East Jerusalem, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai in the Six-Day War of 1967. This of course only amplified the prestige that accrued to the Palestinian fedayeen when they defeated an Israeli invasion of Jordan at the 1968 Battle of Karameh. Suitably emboldened, they went on to launch a full-scale revolt against the Jordanian monarchy in 1970 – with China’s full-throated endorsement, as Radio Peking exhorted them to “fight on against the Jordanian military clique and their American militarist masters until final victory.”

This “Black September” uprising ended in catastrophe, with PLO forces thoroughly routed and expelled from all their territorial bases in Jordan. Afterwards, China markedly dialed down its sponsorship for such insurrectionary activity and turned towards rebuilding state-to-state relationships with Arab governments. This proceeded in tandem with its budding rapprochement with the United States and its 1971 entry into the UN, carried atop a wave of support from African and Arab states (and, interestingly, Israel). Nonetheless, China remained Palestine’s most steadfast ally among the great powers. During the 1973 Arab-Israeli War it stood alone in refusing to endorse UN Security Council Resolution 338 on the grounds that it failed to “explicitly provide for the restoration of the national rights of the Palestinian people,” and later boycotted the Geneva peace conference for excluding Palestinian representatives. In keeping with its ideological polemics against Soviet “revisionism,” China denounced the USSR’s support for negotiated Arab-Israeli peace settlements in both 1967 and 1973 as a great-power betrayal of the Palestinian cause.

Throughout all these twists and turns, popular manifestations of Chinese solidarity with the Palestinian liberation struggle continued unabated. Beginning in 1965 with the first PLO visit to Beijing, Nakba Day (May 15) was officially designated as “Palestine Solidarity Day” and commemorated annually with mass public rallies of 100,000 or more in Tiananmen Square. The short propaganda documentary “巴勒斯坦人民必胜” (“The Palestinian people must win,” 1971) features newsreel footage of enormous demonstrations against the 1956 Suez Crisis and the 1967 Six-Day War, including people’s delegations to the embassies of Palestine, Egypt, and Syria. Similarly large crowds are shown greeting Yasser Arafat on his 1970 visit to Beijing.

Belying the Western image of China during the Cultural Revolution as a closed and xenophobic society, people-to-people connections were also forged at a more profoundly intimate level. The aforementioned Ghassan Kanafani, for example, traveled to China and India in 1965 and documented his experiences in a little-known revolutionary travelog entitled «ثم أشرقت آسيا», or “Then Asia Shone.” During the Chinese leg of his journey he visited Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou, meeting with Marshal Chen Yi and recording his observations not just of landmarks like Tiananmen Square and the Great Wall but also of mosques and agricultural collectives. Pondering the preserved monuments of the imperial past, he saluted the country's long tradition of rebellion: “If I were Chinese, my admiration for what the emperors did for themselves would be exceeded only by what the people did to the emperors!” His comments on poverty were equally moving and prophetic:

Poverty, if we want to use a more brutal word, is that ogre which has ravaged China throughout its long history and which the revolution has not yet been able, due to its age and China’s many problems, to turn into a servant, but has successfully put in a cage ... It seems that the vitality of the revolution and its desire to mobilize human energy runs ahead of its financial capacity, and the Chinese are proud of what their bare hands can do while awaiting the future, when they are confident they will be able to finance their well-being. They have put to work the 1,300 million arms they have to build the road to the future without a moment of waiting.

Kanafani’s literary compatriot Abu Salma, a poet who went on to chair the General Union of Palestinian Writers and Journalists, was similarly moved while visiting China to write the following lines (as quoted by Yin Zhiguang):

We have fought the same fight.

We have endured the same suffering.

Now we’re in Beijing.

We can spread our wings and fly.

The strong people here

all have sprouted wings.

We are united in our struggle,

The glory will be ours!

We shall wear laurels on our heads,

And smiles on our faces.

When dark clouds cover the firmament,

A wild wind sweeps through the universe.

When Mao’s smile appears on the horizon,

Earth’s skies become clear for miles and miles!

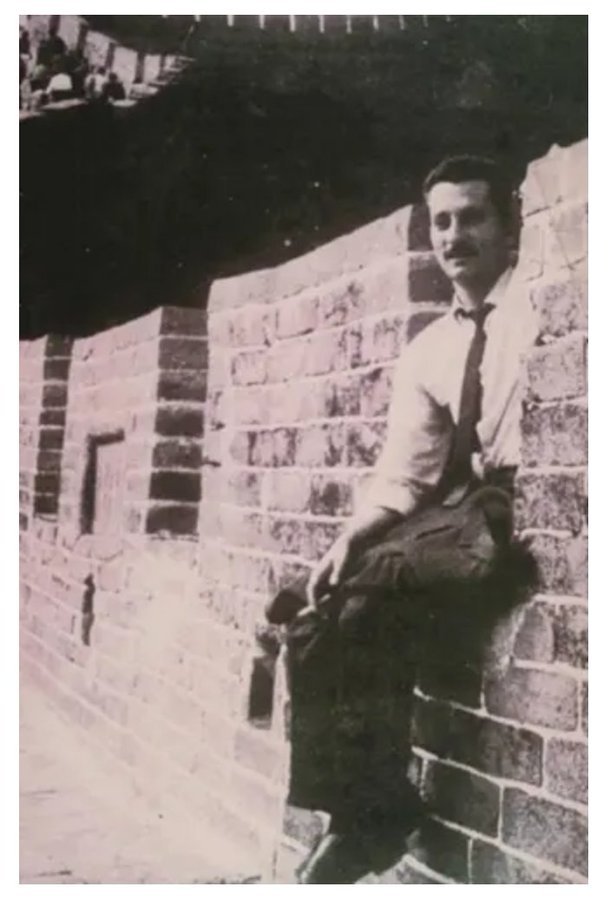

Ghassan Kanafani on the Great Wall, 1965

Beyond such temporary visits of a personal or diplomatic nature, a small but enduring Palestinian expatriate community also formed in China, mostly comprising dissident journalists and intellectuals exiled by hostile Arab host governments. The PRC also offered scholarships to several dozen Palestinian students per year, creating a community sufficiently robust to form the General Palestinian Students’ Union in 1981. As recounted by Mohammed Turki al-Sudairi, these students remained politically active even after the Cultural Revolution’s high tide of mass mobilization ebbed: “major protests and rallies were held throughout 1979, 1980, 1982, and 1983 in connection with such regional events as the signing of the Camp David Accords by Egypt, the American bombing of Libya, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and turning points in the Lebanese civil war such as the Sabra and Shatila massacres.”

These events charted an inexorable direction of travel for China in its relations with the PLO, which since the 1974 Arab League Summit had been designated the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.” It was a path prophetically laid out by Lillian Craig Harris as early as 1977, when she wrote: “Whether China would consider the Palestinians to have ‘sold out’ if they accepted a West Bank state with agreement against attacks on Israel to secure more territory is another question. Yet indications are that Chinese pragmatism could stretch to swallow even a non-revolutionary Palestine if the benefit for China were a state with which it entertained good relations.”

That is indeed exactly what happened with the 1988 Palestinian Declaration of Independence, which implicitly acknowledged the 1947 UN Partition Plan and retreated from the PLO’s express commitment to a one-state solution. As in 1965, but with considerably less fanfare, China was one of the first non-Muslim-majority countries to recognize the newly declared State of Palestine. By the time Arafat signed the Oslo Accords in September 1993, extending unreciprocated recognition to Israel and abandoning all claim to 78% of historic Palestine, China had already had diplomatic relations with the Zionist state for over a year. It was just one of around 25 predominantly socialist, ex-Soviet, and/or former Eastern Bloc countries that had done so since the fall of the USSR and the nearly simultaneous initiation of the “peace process.” The PLO’s capitulation at Oslo simply provided ex post facto cover for the vast majority of Palestine’s non-Arab allies to follow it into normalization.

China’s role in this process, while hardly atypical, did involve a number of ironic historical peculiarities. One was that it had initiated informal economic ties with Israel years prior to the formal establishment of diplomatic relations, largely as a means to evade Western arms embargoes imposed after the 1989 Tiananmen protests. (Israeli-sourced military technology had the added benefit of being extensively battle-tested against Soviet weapons systems in the course of numerous wars against Arab states.) For Israel’s part, then-Deputy Foreign Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was reported in November 1989 to have said, “Israel should have taken advantage of the suppression of the demonstrations in China, while the world’s attention was focused on these events, and should have carried out mass deportations of Arabs from the territories. Unfortunately, this plan I proposed did not gain support.” Needless to say, it would not be his last chance.

Another irony which has acquired supreme importance since October 7, 2023 is that a broad and ideologically diverse coalition of Palestinian resistance forces has at long last achieved the kind of operational unity that Mao-era China had always dreamed of. Gaza’s Joint Operations Room spans an ideological range much broader than that represented at any time in the PLO, running from Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad to the Marxist-Leninist PFLP and DFLP. Yet this united front formed in explicit opposition to the Fatah-led PLO, and its main external sponsor is not China but the Islamic Republic of Iran – also heir to an anti-imperialist revolution but of markedly different character.

All this said, China maintains warm symbolic ties to a number of these formations, as does the CPC with the Marxist ones on a party-to-party basis. The latter in turn have reciprocated, for example by publicly endorsing China’s policy in Hong Kong (see statements by the PFLP and DFLP) and more recently hailing its diplomatic efforts to secure a ceasefire in Gaza. Despite intra-Palestinian tensions over normalization and security cooperation with Israel, these positions are broadly in line with the State of Palestine’s official opposition to “interference in China’s internal affairs under the pretext of Xinjiang-related issues.” As the world watches in horror the incontrovertible scenes of genocide relayed in real time from Gaza, this stance on Xinjiang – while hardly atypical for the Global South – stands in stark contrast with the small but vocal minority of diaspora Uyghur separatists who expressed admiration for Zionist ethnonationalism and voiced solidarity with Israel after October 7.

With the genocide entering its sixth month, official rhetoric from China has also recently taken a harder and more overtly pro-resistance edge. Most notably, at a February 2024 International Court of Justice hearing on the legality of the Israeli occupation, PRC Foreign Ministry legal advisor Ma Xinmin made waves by affirming that the “Palestinian people’s use of force to resist foreign oppression and complete the establishment of an independent state is an inalienable right.” Citing UN General Assembly Resolution 3070 of 1973 – inscribed into international law at the high tide of anticolonial struggle – he reiterated the legitimacy of Palestinian resistance “by all means, including armed struggle,” which is categorically “distinguished from acts of terrorism.” For its part, Hamas quickly responded by expressing its appreciation for this uncharacteristically bold intervention.

There is also a strong case to be made that China’s more methodical diplomatic approach in the post-Mao era – coupled with its growing challenge to US hegemony under Xi Jinping – has helped shape a more propitious regional environment for the Palestinian resistance. Helena Cobban, for instance, asserts that “the Beijing-aided reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran transformed the politics of the entire Gulf/West Asia region, and in some ways made the October 7 action more feasible for Hamas’s leaders. The reconciliation reestablished China as a power with major influence within West Asia after an absence of more than five hundred years … the crisscrossing relationships that had been built up among BRICS members old and new provided a rich network of ‘postcolonial’ solidarity for the anticolonial national liberation struggle Hamas’s leaders and supporters saw themselves as fighting.”

All this said, it remains a common sentiment within China’s anti-imperialist left that, in the words of Yin Zhiguang, “with the demise of ideological politics within China, the discursive influence once achieved by New China's diplomacy is also fading.” In a message to the author, Zhang Sheng reiterated this point even more forcefully: “Mao era China's support for Palestinian people's righteous struggle for liberation is one of the most glorious pages of the PRC's history of internationalism, and I still feel proud and inspired today reading about this period of history. Until today, China is still a true friend of Palestine, and we will always stand in solidarity with the Palestinian people's struggle for liberation and self-determination. Unfortunately, I have to painfully admit that some of these glorious traditions have faded away after the Reform, and I truly wish that China could have done more to speak out against Israeli invasions and against the ongoing genocide in Gaza.”

In other words, we must look beyond the staid realm of official statements and state-to-state relations in order to truly understand the significance of China and the rise of multipolarity for the Palestinian resistance after October 7. In the remainder of this essay we will turn towards other, deeper manifestations of the indissoluble bond between both peoples and their respective revolutionary processes.

Part II: Al-Aqsa Flood, or People's War in the New Era arrow_upward

Palestinian guerrilla fighters in Jordan studying Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, 1970

Mao Zedong says: the enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue. His theorizing on guerrilla warfare can be described as the flea war.

The conundrum of “how would a nation that is not industrial win over an industrial nation” was solved by Mao. Engels saw that nations that are able to provide capital are more likely to defeat [their] enemies. Meaning that economic power has the final word in battles because it provides the capital to manufacture arms. Mao’s solution however was to emphasize non-physical (or non-material) elements. Powerful states with powerful armies often focus on material power; arms, administrative issues, the military, but according to Katzenbach, Mao emphasized time, space (ground), and the will. What that means is to avoid large battles leaving ground in favor of time (trading space/ground with time) using time to build up will, that is the essence of asymmetrical war and guerrilla war.

— Basel al-Araj, “Live Like a Porcupine, Fight Like a Flea” (2018)

Notwithstanding Mao’s admonition to his PLO visitors to avoid book worship – including and especially of his own works – his writings on guerrilla warfare had by then become canon, and for good reason. Xinhua News Agency reported that the theoretical syllabus for Palestinian guerrillas training in China included "Problems of Strategy in China's Revolutionary War" (on the 1927-36 phase of the civil war between the CPC and KMT) and “Problems of Strategy in Guerrilla War Against Japan” (on the CPC’s need to maintain guerrilla tactics even in an anti-Japanese United Front with the KMT).

Even as the ideological coordinates of the Palestinian armed struggle moved away from the left-nationalism and Marxism of the 1960s-70s and in a more Islamist direction, the precepts of people’s war retained a timeless quality. Time and again they were taken up (sometimes piecemeal) and creatively adapted to suit contemporary conditions, as in the above passage from polymathic revolutionary intellectual and martyr Basel al-Araj. The current conjuncture in the wake of Operation Al-Aqsa Flood is no different – five months at the time of writing into Israel’s genocidal assault on the people of Gaza, which has slaughtered well over 30,000 martyrs but left the resistance and its fighting capacity stubbornly and miraculously intact.

In this section we aim not to provide a detailed military assessment of the Gaza war and its broader regional repercussions, for which we are eminently unqualified, but to explore some of its key dimensions through the lens of Mao’s writings on guerrilla war. We take as our point of departure the analysis of our comrades in the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM), who characterize Gaza as simultaneously (and perhaps at first glance paradoxically):

An open-air prison or concentration camp, already subject to near-genocidal siege conditions prior to October 7 and now converted into a mass death camp;

The foremost popular cradle of the Palestinian revolution, i.e. “the organ, the beating heart, by which Palestinian resistance is carried out against the Zionist enemy”;

The “only liberated Palestinian territory” and viable base area for large-scale resistance operations, starting with Israel’s 2005 “disengagement”;

And the focal point of the regional Axis of Resistance.

Given the unspeakable horrors transmitted daily from Gaza’s killing fields, the first characterization now utterly dominates mainstream conceptions of the enclave. But Palestinians more than anyone else – even and especially those suffering directly under this murderous onslaught – are adamant that it not be allowed to monopolize our understanding of Gaza’s place at the heart of the struggle. To that end we now consider each of the others in turn.

Gaza as popular cradle

Many people think it impossible for guerrillas to exist for long in the enemy's rear. Such a belief reveals [a] lack of comprehension of the relationship that should exist between the people and the troops. The former may be likened to water, the latter to the fish who inhabit it. How may it be said that these two cannot exist together? It is only undisciplined troops who make the people their enemies and who, like the fish out of its native element, cannot live.

— Mao Zedong, Chapter 6 of “On Guerrilla Warfare” (1937)

Mao first posed this famous metaphor with guerrilla fighters as his audience, in a context where (especially during the civil war) they frequently had to contend with anti-communist ideological conditioning and mass suspicion of all armed formations as “bandits.” While the comparison with the Palestinian armed resistance is inexact, its deep level of implantation within the fabric of society for over 75 years is by no means an automatic byproduct of Zionist oppression. It requires careful and intentional cultivation, and in this sense we can think of the popular cradle as a complementary doctrine for the masses themselves: on how to act collectively as the “water” within which the guerrillas swim.

The Palestinian Youth Movement defines the concept thusly: “The Popular Cradle works as the organ of our struggle by conceptualising resistance as both a normal and necessary state of being and creating a resistance-enabling environment in which the popular masses financially, socially, and politically sustain the resistance and readily accepts the consequences of supporting armed struggle against Zionist settler colonialism.” Historical instances of the popular cradle in action include the widespread adoption by civilian men of the now-ubiquitous keffiyeh, over the then-customary Ottoman-style fez, in order to help armed revolutionaries blend into crowds during the Great Revolt of 1936-39. A more recent example in the same spirit occurred in 2022, when hundreds of men in the West Bank refugee camp of Shuafat shaved their heads in order to thwart Israeli efforts to apprehend or kill the bald resistance fighter Udai Tamimi.

In their analysis PYM considers the entirety of the Gaza Strip to constitute a single, massive popular cradle for the resistance – at a qualitatively larger scale than is practicable in the territorially-fragmented West Bank under the collaborationist Palestinian Authority. As Max Ajl writes, the extraordinary heroism and sumud (steadfastness) of Gazan civilians under Israel’s genocide vindicates this judgment resoundingly: “the popular cradle brings the word resistance beyond armed men to doctors going to their deaths in lieu of abandoning their patients and women and men in the Gaza Strip’s North – facing white phosphorus rather than abandoning their homes. It is precisely the strength of the civilian commitment to the national project that provokes US-Israeli extermination … to break Hamas by breaking its cradle.”

Another, more quantitative measure of the popular cradle’s endurance can be derived from public surveys of Palestinians before and after October 7. Of course even in “ideal” conditions, to say nothing of those currently endured by Palestinians in both Gaza and the West Bank, such polls have major limitations as meaningful barometers of mass sentiment. Nor do their results necessarily reflect the dialectical process through which the masses form a collective political subject in the course of true people’s war. With all these caveats, however, it is undeniable that Al-Aqsa Flood catalyzed a qualitative upsurge in the popular embrace of armed resistance. Two months into the war, the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research recorded a doubling of support for Hamas (from 22% to 43%) and a dramatic increase in support for armed struggle generally (from 41% to 63%) compared with surveys before October 7.

This remarkable outcome strongly recalls Amílcar Cabral’s trenchant observation that in Guinea-Bissau’s unfavorably flat physical terrain – a problem even more acute for Palestinian guerrillas – “the people are our mountains.” Returning to the Chinese example, the triumphs and travails of the resistance since October 7 also evoke Edgar Snow’s moving summation of the Long March in Red Star Over China:

In one sense this mass migration was the biggest armed propaganda tour in history. The Reds passed through provinces populated by more than 200,000,000 people … Millions of the poor had now seen the Red Army and heard it speak, and were no longer afraid of it … Many thousands dropped out on the long and heartbreaking march, but thousands of others – farmers, apprentices, slaves, deserters from the Kuomintang ranks, workers, all the disinherited – joined in and filled the ranks.

Gaza as liberated territory

The problem of establishment of bases is of particular importance. This is so because this war is a cruel and protracted struggle. The lost territories can be restored only by a strategical counter-attack and this we cannot carry out until the enemy is well into China. Consequently, some part of our country — or, indeed, most of it — may be captured by the enemy and become his rear area. It is our task to develop intensive guerrilla warfare over this vast area and convert the enemy's rear into an additional front. Thus the enemy will never be able to stop fighting. In order to subdue the occupied territory, the enemy will have to become increasingly severe and oppressive. A guerrilla base may be defined as an area, strategically located, in which the guerrillas can carry out their duties of training, self-preservation and development. Ability to fight a war without a rear area is a fundamental characteristic of guerrilla action, but this does not mean that guerrillas can exist and function over a long period of time without the development of base areas.

— Mao Zedong, Chapter 8 of “On Guerrilla Warfare” (1937)

The aforementioned Long March was in many ways the paradigmatic example of the conception of strategic depth that Mao articulates here. In that grueling ordeal the Communists maximally exploited the sheer vastness of China’s territory, as they would do again after Japan’s invasion. On the other hand the applicability of this passage to a besieged coastal enclave just 25 miles long and five miles wide, with one of the highest population densities on earth, may not be immediately obvious. But if we examine the long arc of Palestinian struggle at multiple spatial and temporal scales, this principle indeed comes into operation time and again.

It could be argued that up until the First Intifada erupted in Gaza’s Jabalia refugee camp in 1987, Palestinian guerrillas faced the opposite conundrum from that spelled out by Mao. That is to say, after the successive blows of 1948 and 1967 the entirety of historic Palestine came under Zionist occupation, with virtually all Palestinians therein under nearly undifferentiated military rule. This essentially left organized guerrilla formations with only rear areas – mainly refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan – and little to no frontline or base area to speak of within occupied Palestine itself. (One of the few exceptions, in a further testament to Gaza’s centrality to the resistance, was a series of Egyptian-sponsored raids originating from the territory in the lead-up to the 1956 Suez Crisis: a distant historical precursor to Al-Aqsa Flood.)

During this earlier period, resistance groups had to creatively adapt the precepts of guerrilla war to the conditions of exile. As pointed out in the 1971 documentary Red Army-PFLP: Declaration of World War (on which more in Part IV): “They make no distinction between front line and rear … for them there is no difference between urban guerrillas and [rural] guerrilla warfare. Urban guerrillas learn on the battlefield, and masses of people make the battlefield their home.” At another point in the film, a PFLP cadre explains that “it is here, the Jerash Mountains stretching along the border between Israel and Jordan, that we choose to be our battleground, to build our base to start war and expand revolution.” The reasoning behind this decision – to build a base sandwiched between two (at the time) mutually-antagonistic bastions of imperialism – recalls that of Mao in “Why is it that Red political power can exist in China?” (1928): “The prolonged splits and wars within the White regime provide a condition for the emergence and persistence of one or more small Red areas under the leadership of the Communist Party amidst the encirclement of the White regime.”

As recounted in Part I, the crushing of the Black September uprising rendered even this tenuous foothold on the border of Jordan and occupied Palestine impossible to maintain. In subsequent decades a series of military and diplomatic maneuvers by Israel and its imperialist backers, principally the United States, further eliminated one rear area after another in calculated fashion. Chief among these were Israel’s brutal 1982 invasion of Lebanon (to which the PLO had fled from Jordan and from which it was forced to flee again), followed by its 1985-2000 occupation of south Lebanon; and since 2011 the US-led proxy war on Syria, which paid host to multiple rejectionist factions after the Oslo accords. Alongside these came Israel's normalization agreements with Egypt in 1979, Jordan in 1994, and four other Arab states in the 2020 Abraham Accords, as well as the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) as a counterinsurgent force in the occupied territories themselves.

Israel’s unilateral “disengagement” from the Gaza Strip in 2005 would appear to have bucked this trend, though as PYM points out it was motivated more by the Palestinian “demographic threat” to the rather thin Jewish settler presence there. If Zionist authorities also felt secure in entrusting Gaza to the PA for continued “pacification,” they were swiftly disabused by Hamas’s victory in the 2006 legislative election and its subsequent takeover of the territory in 2007, following an abortive Fatah-led coup attempt. These events effectively converted the Strip into a de facto liberated territory and base area – albeit under crushing blockade – where Hamas and other resistance factions could, in Mao’s words, “carry out their duties of training, self-preservation, and development.”

Whether Gaza could be qualified as “strategically located” was another question entirely. Hemmed in from the west by the Mediterranean Sea and on all other sides by the joint Israeli-Egyptian blockade, the apparent lack of strategic depth enjoyed by the resistance – to say nothing of the civilian population – was made painfully clear by a succession of punishing military onslaughts in 2008, 2012, 2014, and 2021 even before the apocalypse of 2023-24.

On paper, this is a far more disadvantageous position than that faced by any CPC revolutionary base area after the Long March. Yan’an, for example, was chosen as the destination of that arduous trek partly for its closeness to the anti-Japanese front and to Soviet supply lines (as well as those from the rest of KMT-held North China after the formation of the Second United Front). And when the civil war resumed in force after World War II, the new CPC base in Manchuria directly bordered both the Soviet Union and north Korea, which offered expansive rear areas and near-inexhaustible supply lines for both men and materiel.

Chinese state media report from November 2, 2023 showing footage released by Hamas of a tunnel-based anti-tank operation

But famously, and more crucially than ever before in the wake of October 7, the Gaza-based resistance has compensated for its conspicuous lack of lateral strategic depth by constructing a gargantuan tunnel network 300 to 450 miles in length (according to the latest Israeli estimates). In other words, as Justin Podur points out, they have literally built vertical strategic depth into the ground. In this way they make up not just for the limited size but also other deficiencies of the physical terrain, as Louis Allday notes: “Gaza’s geography lacks the mountainous and/or dense forested areas that were crucial in other successful guerrilla warfare campaigns—the network of tunnels now effectively fulfills that role.” Max Ajl sums up their combined political, technical, and strategic achievements in terms that echo Cabral: “The resistance … has alloyed ideological commitment, willingness to sacrifice for their people, and technological ingenuity into armed capacity capable of going head-to-head with a nuclear power from underground tunnels, the ‘rear base’ and physical strategic depth needed for guerilla insurgency. The concrete is their mountains.”

Indeed the near-total devastation of Gaza’s built infrastructure – both a byproduct and an intentional manifestation of Israel’s genocidal aims – has turned concrete into “mountains” even above ground as well. Jon Elmer of the Electronic Intifada has highlighted that resistance forces now routinely use the rubble from Israeli airstrikes as advantageous terrain to attack invading ground troops from all angles. At times they even “walk through walls” as former IDF chief of staff Aviv Kochavi once boasted of doing, through homes not yet depopulated of their civilian inhabitants, in his quasi-Deleuzian counterinsurgent operational theory. Even as Israeli forces boldly claim “full operational control” over most of the Strip, penning some 1.5 million civilians into Rafah for what they believe to be a final eliminatory push, the resistance retains its capacity to wage a guerrilla war of maneuver even as far north as Gaza City. Just as Mao prescribed, everywhere they “convert the enemy’s rear into an additional front. Thus the enemy will never be able to stop fighting.”

The Axis of Resistance: encirclement and counter-encirclement

If the game of weiqi is extended to include the world, there is yet a third form of encirclement as between us and the enemy, namely, the interrelation between the front of aggression and the front of peace. The enemy encircles China, the Soviet Union, France and Czechoslovakia with his front of aggression, while we counter-encircle Germany, Japan and Italy with our front of peace. But our encirclement, like the hand of Buddha, will turn into the Mountain of Five Elements lying athwart the Universe, and the modern Sun Wukongs – the fascist aggressors – will finally be buried underneath it, never to rise again.

— Mao Zedong, “On Protracted War” (1938)

When Mao wrote these words a year before the outbreak of World War II in Europe, China’s war of resistance against Japan could justly have been considered the epicenter of the world anti-fascist struggle. It would be no exaggeration to say that Gaza occupies this position today. As such we cannot ignore that as the Zionist “front of aggression” encircles and seemingly lays waste to the very possibility of human life in Gaza, the resistance there compensates for its lack of strategic depth not just through tunnel warfare but through its own “front of peace”: the Axis of Resistance. Primarily comprising the Lebanese resistance formation Hezbollah, the Ansarallah movement of Yemen (also known as the “Houthis”), and the Islamic Resistance in Iraq, the non-Palestinian members of this alliance have since October 7 leveraged their strategic locations and access to state-level resources – and in Ansarallah’s case, de facto state status – to effect an asymmetric counter-encirclement of Israel and its regional backers.

The activities of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq serve to illustrate the recursive nature of “encirclement” in this context. Though their membership substantially overlaps with that of the Iraqi state-sponsored Popular Mobilization Forces, they lack some of their allies’ long-range firepower and have only rarely been able to target Israel directly. But their area of operation includes dozens of US military bases – globally part of a world-encircling network of around 800, but locally quite isolated and exposed. The Islamic Resistance has exploited this fact to maximum effect given its capabilities, launching over 170 attacks on US bases in Iraq and Syria since October 17 in a campaign both to expel occupying forces from the region and to raise the costs for their support of the Israeli genocide. One of these attacks scored a major coup on January 28, 2024 by killing three US troops at the Tower 22 base in Jordan.

More strategically located vis-à-vis Israel, and with decades more fighting experience from its victorious fifteen-year campaign to liberate southern Lebanon and its historic defeat of another Israeli invasion in 2006, is Hezbollah. Starting on October 8, just a day after Al-Aqsa Flood, it has by its own count launched over a thousand cross-border operations mainly against Israeli military bases, surveillance posts, and settlements in the north. According to statements by Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah on January 5 and February 4, Hezbollah has thereby forced the evacuation of 230,000 settlers from northern occupied Palestine; tied down 120,000 Israeli ground troops and fully half of its navy and air force, leaving them unavailable for the assault on Gaza; and inflicted over 2000 direct casualties. According to a recent survey, 60% of Lebanese believe “the presence of the resistance, its demonstration of its growing strength, and its revealing of an important aspect of these capabilities during the current confrontations” are responsible for preventing a comprehensive Israeli attack on the country.

Chinese state media report from November 21, 2023 showing footage released by Ansarallah of their seizure of the Galaxy Leader ship two days earlier

The most creative and unlikely intervention has come from Yemen’s Ansarallah, the de facto governing authorities of a country that has itself suffered eight years of unremitting siege and bombardment from US-backed Saudi and Emirati forces. Since November 18, when they sensationally boarded and captured the Galaxy Leader, they have enforced a blockade on Israeli-bound or Israeli-linked shipping through the Bab al-Mandab strait at the southern end of the Red Sea. In total Ansarallah claims to have targeted at least 48 vessels affiliated with Israel (or the US and UK, since the latter began launching joint airstrikes on Yemen on January 11) and has pledged to continue until the Israeli siege on Gaza ends. Contrary to patronizing Western narratives that paint their actions as mere piracy, Max Ajl emphasizes that “the Yemeni armed forces understand themselves as fighting a mass mobilizing peoples’ war, based on ideological hardening of troops and sophisticated tactics to neutralize technological superiority, learned during their apprenticeship with Hezbollah.”

In an ironic echo of the practice of corporate “over-compliance” with US sanctions on Iran and Cuba, four of the world’s five largest shipping companies have suspended their Red Sea routes entirely. Freight volume passing through the Red Sea has plummeted by a stunning 80% from pre-crisis levels according to the Kiel Trade Indicator; traffic specifically at the southern Israeli port of Eilat has cratered by 85%. Given its centrality to global trade, much attention has focused unsurprisingly on China’s positioning. Its public rejection of US entreaties to join the ill-fated “Operation Prosperity Guardian,” and its condemnation of unilateral aggression against Yemen, is probably not unrelated to the growing trend of vessels signaling “all Chinese crew” to avoid targeting by Ansarallah. Meanwhile state-owned shipping company COSCO has stopped traffic to Israeli ports entirely, following in the footsteps of its Hong Kong subsidiary OOCL and Taiwan-based Evergreen’s refusal to handle Israeli cargo.

According to historian Amal Saad, the Axis of Resistance has thus managed to impose an entirely new like-for-like strategic equation on Israel in the wake of October 7: “displacement for displacement” in the case of Hezbollah, and “siege for siege” for Ansarallah. Together this constitutes a regional counter-encirclement that partially negates any strategic depth Israel may enjoy vis-à-vis Gaza alone, even with the active collusion of its neighbors Egypt and Jordan. Khalil Harb notes the unprecedented nature of this strategic conjuncture: “For the first time in its 76-year history … the occupation state is today grappling with buffer zones inside Israel.”

A common Western smear against the Axis is that its various members act essentially as proxies for their main state sponsor, the Islamic Republic of Iran. Their actual operational practice since October 7 has conclusively refuted this charge. In a January 3 speech commemorating the anniversary of Qassem Soleimani’s martyrdom, Hassan Nasrallah pointed out that the late Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander had always pushed for resistance factions to avoid dependence on Iran and attain material self-sufficiency and operational autonomy – objectives which have now been met. “In this grand vision,” he noted, “no one commands another. We discuss. We share opinions. We learn from each other. But each one decides his own pathway in his own country based on what is good for his country.”

From a technical standpoint, Max Ajl notes, “Iranian weapons and training are free, representing ‘the possibility of access to weapons for the poor.’ Indeed, their blueprints are often open-access or freely shared from Iran to its state and sub-state partners.” This dynamic stands in stark contrast to the dependency that the United States forces on most of its Global South vassals (particularly in the region, e.g. Egypt and Saudi Arabia) as captive markets for its domestic arms industry. Rather it loosely resembles, albeit in an even less transactional form, China’s active efforts to promote industrialization and scaling of the value chain by its partners in the Belt and Road Initiative. Indeed, Matteo Capasso has convincingly argued that China’s single greatest material contribution to Palestinian resistance today is its deepening bilateral trade with Iran, enabling the country to support its Axis partners in building out their autonomous capabilities even under a vicious US sanctions regime.

In Palestine itself this essentially decentralized form of coordinated resistance has been mirrored in the “unity of the fields” between Gaza, the West Bank, and the ‘48 territories. With the Unity Intifada of May 2021, “for the first time in nearly two decades, Palestinian resistance, whether armed or unarmed, was no longer confined to a single territorial enclave.” Unfortunately that volume of open resistance within ‘48 Palestine has not been matched since October 7, owing to depoliticization and normalization within nearly all nominally legal Palestinian formations. But the year 2023 did witness a remarkable 350% increase in West Bank resistance operations over the previous year, from 170 to 608.

Regarding the unity of the fields, in terms that apply equally to the broader regional practice of the Resistance Axis since October 7, Abdaljawad Omar remarks aptly that

This ambiguity means that the occupying state must design its military operations taking into account the possibility of any small confrontation developing into a multi-front regional war. At the same time, the lack of clarity of the concept gives the possibility of evasion, such that the resistance determines when to intervene, or what its red lines are, or when the response will be broad and from all geographies, and when it will be limited and from a specific location, or when there will be no response at all.

Part III: Smashing Walls, Building Firewalls, and Breaking the Digital Siege arrow_upward

In the last section we explored the Axis of Resistance and its pursuit of material self-sufficiency, as well as Basel al-Araj’s incisive Mao-inspired analysis of asymmetric warfare against a technologically superior enemy. Building on that foundation, we now turn to two intentionally under- or misreported facets of the current conjuncture:

The sovereign technological innovations developed by the Palestinian resistance under siege conditions in Gaza, particularly in the fields of weaponry, counterintelligence and counter-surveillance, and information warfare; and

How these are enabled, reinforced, and amplified by China’s own project of sovereign technological development and delinking from Western digital monopolies – a target of renewed opprobrium since the start of the war.

Both phenomena are manifestations, under vastly different circumstances, of what Max Ajl describes in the context of the Resistance Axis as “the dialectical relationship between technological upgrading, defensive industrialization, and armed defensive capacity to secure the space for expanded reproduction in peripheral or embattled nation-states.”

Since October 7 the Qassam Brigades (the armed wing of Hamas) have released a near-daily stream of videos displaying an impressive range of indigenously developed weaponry. Most feature their use in active combat, while some actually show selected aspects of the development, manufacture, and/or testing process. Perhaps the most paradigmatic example – and by far the most visible from the privileged standpoint of Israeli settlers, especially before October 7 – is the vertiginous rise in sophistication of Hamas’s rockets. These have evolved from the first-generation Qassam Q-12, which had a maximum range of around 12 kilometers, to the recently unveiled Ayyash-250 whose 250-kilometer range puts essentially all of occupied Palestine within reach.

Other indigenously produced weapons have made frequent appearances in ground combat; most have been ingeniously adapted based on prior designs from past and present allies of the Palestinian resistance. The Yassin anti-tank rocket-propelled grenade, for example, is based on a modified Soviet model and features in almost every Qassam combat video. The Shawaz explosively formed penetrator, specially designed to penetrate Israeli vehicles’ reinforced armor, is believed to be inspired by devices used by the Iraqi resistance against the 2003-2011 US occupation. And the al-Ghoul sniper rifle, whose manufacture and testing feature prominently in a Qassam video from late December, is based on the Iranian AM50 Sayyad design.

Great historical significance attaches to many of these weapons’ names. Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, the revolutionary cleric who initiated the Great Revolt of 1936-39, gave his name both to the Brigades and to several generations of their iconic rockets. Sheikh Ahmed Yassin co-founded Hamas in 1987. And Yahya Ayyash and Adnan al-Ghoul were both leading engineers who pioneered the Qassam Brigades’ bomb and missile development programs, martyred in 1996 and 2004 respectively. Indeed the organization’s engineering prowess is no accident: as Abdaljawad Omar points out, it was actually a product of their religious conservatism in a way that may strike Western observers as paradoxical, given the strong post-Enlightenment association of science and technology with secularism. In the Palestinian context, Hamas regarded the humanities and social sciences (with some reason) as vectors of Western influence and bastions of the political left, and thus preferentially steered its student cadres into engineering and the “hard” sciences.

This remarkably prescient decision preceded by decades the Hamas takeover and Israeli siege on Gaza, which respectively enabled and necessitated the development of such an expansive indigenous weapons industry. In its logic and foresight we can find distant though compelling echoes in the developmental strategies pursued by China in recent decades. For example the Four Modernizations (in agriculture, industry, defense, and science and technology), proposed by Zhou Enlai in 1963 and officially adopted in 1977, set a technocratic direction of travel for Deng Xiaoping’s reforms after the “ultra-left” ideological upheaval of the Cultural Revolution. More recently, we can observe an intriguing parallel with the rising influence in Chinese online discourse of the so-called “Industrial Party,” which advocates “pure” technological developmentalism as a nominally non-ideological alternative to both the Maoist and New Left and the liberal Right (both of which it categorizes pejoratively as the “Sentimental Party”).

Another constant throughline in the history of Gaza’s homegrown arms industry is the ingenious sourcing of materials repurposed from former and current colonial foes. Specifically, a 2020 Al-Jazeera documentary revealed that the Qassam Brigades have routinely recycled unexploded shells left over from previous Israeli bombing campaigns, and even from wrecked British warships that were sunk off the coast of Gaza during World War I. They have also produced rocket casings using pipes that were installed during the pre-2005 occupation to siphon water into Israel from Gaza’s heavily depleted aquifer. Per a recent report in the New York Times, Israeli intelligence officials believe that “unexploded ordnance is a main source of explosives for Hamas,” particularly those used to devastating effect on October 7. Between this recycling and outright expropriation from Israeli bases, they admit, “we are fueling our enemies with our own weapons.”

In this respect too we can discern a historical irony reminiscent of the Chinese experience. In the final phase of the civil war, the nascent People’s Liberation Army captured billions of dollars’ worth of US weapons supplied to the KMT; one veteran recalled that “nearly 95 percent” of the arms displayed in the 1949 victory parade were of Western or Japanese manufacture. In subsequent decades, China would rely on Soviet models as the basis for a domestic arms industry that it eventually employed to defend against potential attack from the Soviets themselves. With the vertiginous rise and equally dramatic collapse in relations with the United States, this cycle then repeated itself with Western prototypes – partially sourced from Israel itself, as noted in Part I, due to reliable battle-testing against Soviet systems.

These advances in resistance arms production – miraculous as they were, especially under Gaza’s extreme conditions of technological dependency and de-development even before October 7 – obviously could not come close to matching the enemy. Indeed Israel has long distinguished itself not only as the region’s only nuclear-armed state, and by far the world’s largest recipient of US military aid, but as a self-styled “startup nation” at the cutting edge of high-tech surveillance, information warfare, counterinsurgency, and the automation of mass death. Just as crucial to the success of Al-Aqsa Flood as Hamas’s own capabilities were their efforts to conceal them, and to neutralize Israel’s advantages by cultivating a false sense of security in its own insuperable technological dominance.

Nowhere was the Zionist regime more spectacularly humbled for this colonial hubris than in the simultaneous disabling of the Iron Dome and the Gaza “smart wall” on October 7. In a combined arms operation executed simultaneously at over thirty distinct locations, the former was overwhelmed by rocket fire, which “drowned out the sound of gunfire from Hamas snipers, who shot at the string of cameras on the border fence, and explosions from more than 100 remotely operated Hamas drones, that destroyed watchtowers.” After the wall was breached, so precise was the Qassam Brigades’ intelligence that within an hour they had overrun eight military bases including the one housing the elite signals intelligence Unit 8200. At every location their first step was to cut off communications, in a poetic reversal of the blackouts Israel has so routinely inflicted on Gaza before and since.

Those blackouts were just one manifestation of Israel’s near-total control over and intentional de-development of Gaza’s communications system. As Nour Naim writes in her essay “Artificial Intelligence as a Tool for Restoring Palestinian Rights” (in Gaza Writes Back, 2021): “The dependence of the Palestinian infrastructure on Israel’s infrastructure, whether that entail the internet, landlines, or cellular communications, has given Israel as an occupying power enormous monitoring capabilities.” In order to conceal the years of preparation that laid the groundwork for October 7, the resistance adapted accordingly in a way that exploited Israel’s own narcissistic techno-solutionism. As the Financial Times reports, “Hamas has maintained operational security by going ‘stone age’ and using hard-wired phone lines while eschewing devices that are hackable or emit an electronic signature.”

Elsewhere in her essay, Naim notes that “while Israel uses 5G technology and prepares for 6G, Israeli restrictions limit people in Gaza to 2G.” This practice recalls the United States’ largely failed efforts to thwart the large-scale deployment of 5G infrastructure by Chinese firm Huawei, especially throughout the Global South. Its parallel campaign to force Huawei out of at least Western smartphone markets through sanctions and export controls proved rather more successful. As with Israel – albeit with less extreme methods and more global scope – both moves quite transparently aimed to de-develop an enemy while preserving US surveillance capabilities in its captive export markets. (Amusingly, the resulting lack of direct Western experience with Huawei phones led to unfounded speculation that Hamas had used them to evade Israeli surveillance – an incredible marketing pitch if it were only true!)

In the wake of the utter debacle suffered by the entire Israeli state apparatus on October 7, various exculpatory narratives have arisen in order to absolve key actors of responsibility. One floated in the New York Times by self-interested “dissident” officials, which nonetheless arguably has some measure of validity, is that Benjamin Netanyahu intentionally helped “prop up” the Hamas administration in Gaza for most of his time in office. As the claim goes, he hoped to keep the organization “focused on governing, not fighting,” entrenching the political divide with the Fatah-led West Bank and foreclosing the possibility of a viable Palestinian state. Hamas for its part was perfectly content to appear “contained” while using the breathing room thus acquired to plan for Al-Aqsa Flood.

Here again we see a loose though compelling parallel with China, in particular the decades-long US strategy of “engagement” beginning with President Nixon’s rapprochement in the early 1970s. There the intent was to further entrench the already terminal Sino-Soviet split within the socialist camp, directly enlist the PRC into a US-led anti-Soviet bloc, and contain it for the foreseeable future to the periphery of the capitalist world system. China, conversely, appeared to accede to this plan while conscientiously pursuing a complementary strategy of “hiding its strength and biding its time” (韬光养晦) – with results that are now plain for all to see.

Incidentally, per the aforementioned New York Times story, one concrete form of assistance allegedly rendered by Netanyahu was to cover up a “money-laundering operation for Hamas run through the Bank of China.” This was an early-2010s instantiation of what has since October 7 become a veritable cottage industry of Western media narratives accusing China of direct material support for the Palestinian resistance. For the anti-imperialist left such stories may serve as a form of wish-fulfillment, but we must of course recognize their primarily Sinophobic function in an ideological environment that normatively and legally equates resistance with “terrorism” of a distinctly “antisemitic” nature.

On the more substantive end of the spectrum, there are strong indications that many of the relatively inexpensive drones used to disable the Gaza “smart wall” on October 7 were sourced from Chinese commercial manufacturer DJI. If true, as seems highly plausible, this simply testifies to China’s economies of scale and the transformative leveling effects of asymmetric drone warfare in general – also on prominent display in Ansarallah’s celebrated use of $2000 drones, each of which the US Navy requires a $2 million missile to intercept. A similar dynamic is at play with reports from Israeli TV channel N12 claiming that the occupation army had discovered a “‘massive’ cache of Chinese-made weapons being used by Hamas militants in Gaza.” Even this highly questionable source admitted that the origin of this alleged arsenal was most likely the large second-hand and/or black market rather than direct provision approved by the Chinese state.

More speculatively, the notorious Israeli “China watcher” Tuvia Gering has suggested that Ansarallah’s anti-ship ballistic missiles are based on a decades-old Chinese design, the HQ-2, adapted by Iran into the Fateh-110 and supplied to Yemen in modified form as the Khalij Fars-2. (He derives this assessment from a self-described Chinese “military analyst” on Douyin whose actual qualifications are in question.) Whatever the case may be, the US navy has claimed that Ansarallah is the first entity ever to use such missiles in combat. If so, this would join the “first known instance of combat occurring in space” as a most unlikely technological milestone by Yemen, the poorest country in the Arab region and one of the only de facto state governments in the world acting fully on its obligations under the Genocide Convention.

Other reports in Israeli media highlight the growing perceived “security threat” from the country’s extensive economic entanglement with China, an ironic consequence of the latter’s drive toward full normalization starting in the 1990s. One such story claimed that Israeli electronics firms have since October 7 faced significantly heightened “bureaucratic obstacles” from PRC-based suppliers: “The Chinese are imposing a kind of sanction on us. They don't officially declare it, but they are delaying shipments to Israel.” A co-founder of Shin Bet’s cyber unit has also warned that “when it decides the time is right, China may be able to stop the operations of critical infrastructures in Israel,” such as the Chinese-operated port of Haifa.

Within the repressive domestic political environment of the United States, on the other hand, a more insidious narrative has emerged that sees a controlling Chinese hand behind the vast and sustained outpouring of popular solidarity with Palestine. This has included innumerable campus walkouts and sit-ins, dramatic traffic stoppages, direct actions targeting weapons manufacturers and other institutions complicit in Zionist genocide, and mass mobilizations including two marches in Washington, D.C. that drew 300,000 to 500,000 people. As early as October 2023, former Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi was recorded telling pro-ceasefire protestors to “go back to China where your headquarters is” – referencing a notorious New York Times hit piece from August which smeared numerous anti-imperialist organizations as CPC front groups, including protest organizers Code Pink.

Pelosi’s almost cartoonishly McCarthyist jibe hewed closely to what has been probably the most enduring genre of Sinophobic narratives since October 7. These are specifically directed at China’s remarkably successful project of safeguarding its digital sovereignty by building the so-called “Great Firewall,” delinking from Western platform monopolies, and carefully cultivating its own domestic platforms especially for social media. (Indeed the University of Bonn’s Center for Advanced Security, Strategic and Integration Studies ranks China second only to the United States in its “Digital Dependence” index.) In mainstream Western media these features of the Chinese internet are almost universally derided as the creations of a paranoid and totalitarian surveillance state, with an all-encompassing censorship apparatus that enjoys near-total control over online public expression.

In fact this narrative stems from seething resentment that China has created a media and information environment for over a billion internet users that is relatively insulated from Zionist hasbara and entirely free from Western platform censorship. (Admittedly, and inevitably given the size of its user base, the Chinese internet does have its own share of pro-Israel influence operations. But their actual impact has been sharply delineated along class lines, and largely restricted to an increasingly embattled stratum of “rightist” intellectuals still enamored with the civilizational discourses of Western liberalism.) This general phenomenon also manifests to some extent outside China, with Palestinian resistance factions like the Qassam Brigades and Saraya al-Quds enjoying relatively unrestricted access to Russia-based Telegram as a platform for their communications. The contrast with, for example, Meta’s censorship of even “moderate” pro-Palestinian content – so extreme as to draw harsh rebukes even from Human Rights Watch – is painfully obvious.

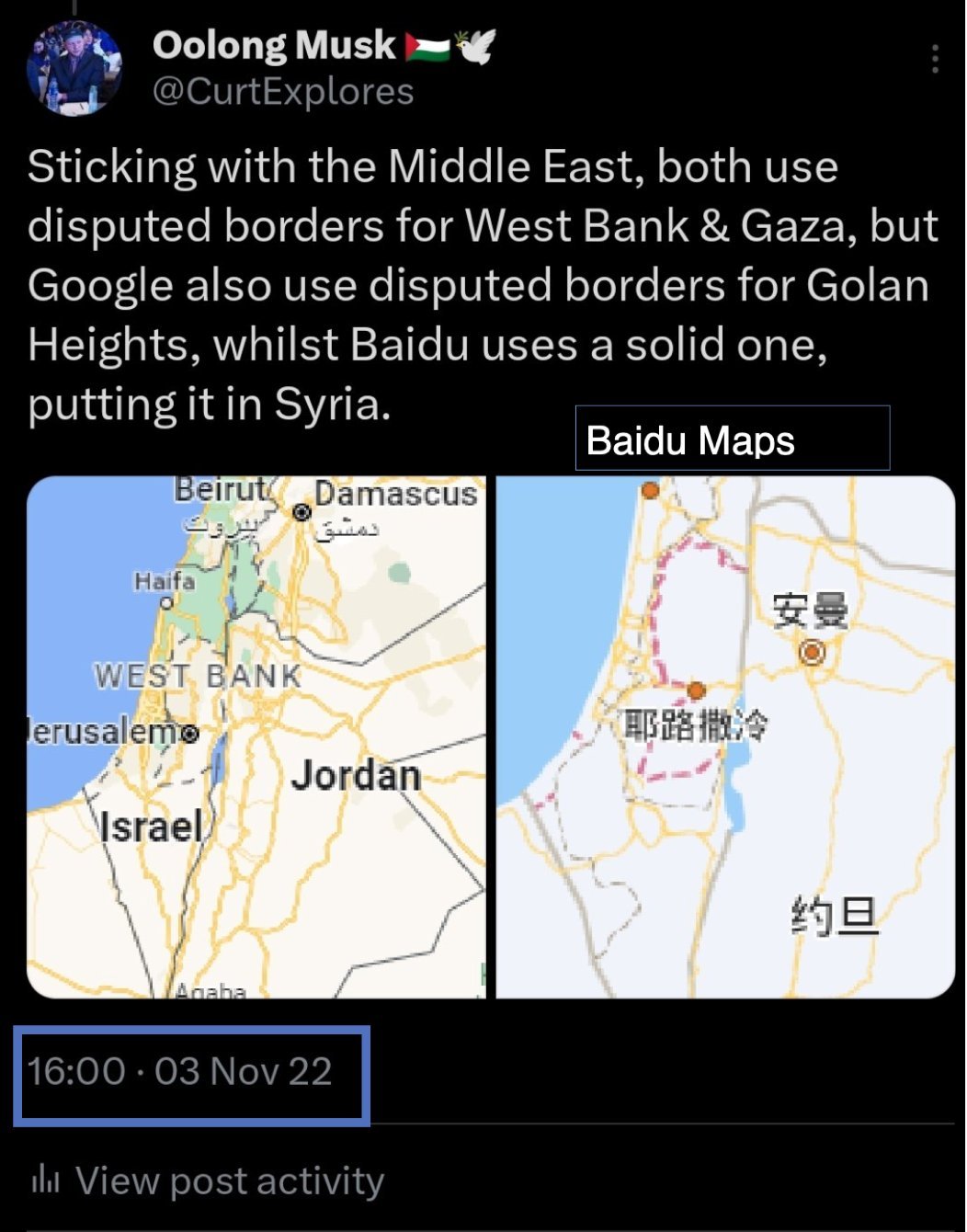

Side-by-side comparison of Google and Baidu Maps’ representations of Palestine and its surroundings

Especially in the fevered early months of Western coverage regarding the war, a number of absurdly overblown stories in this vein gained traction and then rapidly faded away. One of these in early November alleged that two of China’s largest homegrown mapping apps, created by Alibaba and Baidu, had removed Israel’s country name from regional maps in the aftermath of October 7. (The viral claim seems to have originated with a Falun Gong-linked Twitter account and then spread like wildfire to supposedly “reputable” Western media outlets.) The truth was that owing to Israel’s own illegal occupation of the territories seized in 1967, and its calculated refusal to define its own borders, its name had not been visible on either app since at least May 2021. Interestingly, Baidu Maps displays the 1947 UN Partition Plan boundaries in addition to Israel’s much more expansive de facto borders after the Nakba of 1948 – possibly an oblique acknowledgment of the latter’s manifest illegitimacy.

Looking instead at the dominant Western (and global) rival to Alibaba and Baidu Maps, Yarden Katz has shown that a totalizing Zionist settler ideology is firmly embedded in Google’s mapping operations at all levels. In 2013 the company paid $1.1 billion to acquire Waze, which directly “emerged from the Israeli army’s Unit 8200.” Even more consequentially, “Google Maps similarly gives a Zionist view of the land. For Google Maps, Jerusalem is the capital of Israel, and the terms ‘West Bank’ and ‘Gaza’ have in the past been replaced with ‘Israel.’ Google Maps has also displayed large swaths of the West Bank as blanks, reminiscent of Google co-founder [Sergey Brin]’s sense that what isn’t Israel is ‘just dirt.’”

Around the same time, the fallout of October 7 reignited the ongoing Sinophobic witch hunt directed at TikTok due to its ownership by China-headquartered company ByteDance. In an op-ed entitled “Why Do Young Americans Support Hamas? Look at TikTok,” Republican US Representative Mike Gallagher cited a Harvard/Harris poll indicating that a remarkable 51% of Americans aged 18 to 24 believe that the October 7 Palestinian resistance operation was justified. For this “morally bankrupt view of the world,” he placed the blame not on younger generations’ extraordinary political maturity in the face of the Zionist propaganda offensive, but squarely on TikTok: a vector for political socialization supposedly “controlled by America’s foremost adversary, one that does not share our interests or our values: the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).” In a measured but laconic riposte, the company itself was forced to respond by pointing out that “attitudes among young people skewed toward Palestine long before TikTok existed.”

Interestingly, Gallagher extended a backhanded compliment of sorts to China’s attainment of digital sovereignty elsewhere in the article: “We know of TikTok’s predatory nature because the app has several versions. In China, there is a safely sanitized version called Douyin … Put differently, ByteDance and the CCP have decided that China’s children get spinach, and America’s get digital fentanyl.” Putting aside the absurd and racist invocation of a reverse “Opium War,” this line betrays a fundamental unease among Western ideologues – tied to the mast of a rapidly crumbling Zionist hegemony – that the Chinese internet remains, by design, maddeningly beyond their grasp.

Top: “The Great Flood” (大洪水) by Chinese web artist 羊咩咩衣JY, posted to Weibo on October 17, 2023. Bottom: Tribute by Chinese web artist Wuheqilin (乌合麒麟) to US airman Aaron Bushnell.

It should come as no surprise then that the most persistent line of attack on China’s digital sovereignty has directly targeted the country’s netizens, a perennial object of orientalist fascination. In Western media coverage since October 7 two dominant narratives have converged seamlessly: the equation of anti-Zionism with antisemitism, and the supposed unknowability of Chinese public opinion under a totalizing censorship regime. Reporting on a deluge of outraged comments on the Israeli embassy’s official Weibo page, for instance, the New York Times in late October opined: “It is hard to say whether the anti-Israeli positions in state media and antisemitism on the Chinese internet are part of a coordinated campaign. But China’s state media rarely veers from the official position of the country’s Communist Party, and its hair-trigger internet censors are keenly attuned to the wishes of its leaders, quick to remove any content that sways public sentiment in an unwanted direction, especially on matters of such geopolitical importance.”

Another contribution to this genre came from the US state-owned propaganda outlet Voice of America, which in late December reported that “over the past two months, netizens in China have cheered for Hamas and shared cartoons featuring Hamas fighters on Bilibili and other Chinese social media platforms.” The story conveniently neglected to add that said cartoons originated on English-language Twitter, where they received an equally rapturous response before propagating across the Great Firewall. That said, it did acknowledge the growing community of Chinese armchair military analysts who enthusiastically dissect combat videos from the Palestinian resistance for domestic audiences, such as Bilibili user 黑猫星球 (Black Cat Planet) whose work has already graced this article. In this author’s personal estimation, they are every bit the equal of Jon Elmer’s excellent resistance dispatches for the Electronic Intifada.

What such stories actually convey to bona fide anti-imperialists (not VOA’s target audience of course) is just how little fundamentally separates us across national, linguistic, and technological divides. Other examples over the past months include a veritable tidal wave of translations of “If I Must Die,” a poem by martyred Gazan writer and English professor Refaat Alareer, into other languages beginning with one in Chinese. More recently, Chinese netizens saluted the sacrifice of US airman Aaron Bushnell, who self-immolated in front of the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C. on February 25, 2024 in protest of the genocide, with an outpouring of heartfelt tributes and striking visual art.

And try as they might to propagate a narrative of rampant online antisemitism, even Voice of America could not obscure the real historical basis for ordinary Chinese people’s enduring solidarity with the Palestinian cause. “In the comment section of these videos,” the aforementioned story notes, “netizens left messages praising Hamas. They compared Hamas's attacks on the Israeli army to the Chinese Communist Party's counterattack against the Japanese during World War II. One highly liked comment read, ‘It can be said that in them, we can see the figures of the Northeast Anti-Japanese United Army fighters among the white mountains and black waters in the old days.’”

Part IV: Declaration of World War arrow_upward

Now, as in the worldwide revolutionary upsurge of the 1960s-70s, the strongest emotive and analytical connections between China’s historical experience and the Palestinian resistance come through the memory of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Far fewer, in either China or (especially) the West, are likely aware of the contributions made by Japan itself – or rather, a small but impactful minority of Japanese people – in cementing that affective bond in the consciousness of the global left.

Throughout the 1960s Japan was wracked by massive revolutionary upheavals seeking to end its subordination to the United States, which had rehabilitated and largely reinstalled the WWII-era fascist leadership and converted the country into a massive rear base for imperialist aggression against Korea, Vietnam, and China. From these struggles emerged a plethora of armed New Left formations, some of which (most infamously the United Red Army) sadly consumed themselves in fratricidal violence. Seeking a literal way out of these internecine battles, the Japanese Red Army (JRA) was founded in 1971 on a doctrine that sought to expand the armed struggle from its domestic fetters and into the heartlands of world revolution.

As originally formulated by the JRA’s founding chairman Takaya Shiomi, this “international base theory” would have relocated their operations to secure bases in established socialist states, predominantly in the Eastern Bloc. Fellow Red Army leader Fusako Shigenobu soon amended this proposal, arguing that “battlefields of the struggle in transition to liberation and revolution should be our international bases.” Foremost among these active revolutionary battlegrounds in her analysis was Palestine; under her leadership the JRA relocated shortly after its founding to the refugee camps in Lebanon and cemented a close military alliance with the PFLP.

It was just a year later, in May 1972, that the JRA exploded into the popular consciousness and cemented its reputation – for heroism throughout much of the Arab world, and for “terrorism” in the West – by mounting an attack at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv. The operation led to 26 deaths; in an early precursor to the narrative battle surrounding October 7, official accounts paint it as a cold-blooded massacre, while the JRA and other eyewitnesses insist the attackers had a clear military objective (the airport control tower) and most victims were killed in the crossfire. In any case, Zhang Sheng notes that by striking so deep within occupied Palestine the JRA had scored what “was regarded by some as the first victory against Israel, which crippled the myth of Israel’s invulnerability.” The propaganda value of the operation was certainly not lost on Israeli leaders, who months later assassinated PFLP spokesman Ghassan Kanafani and his niece in direct retaliation.

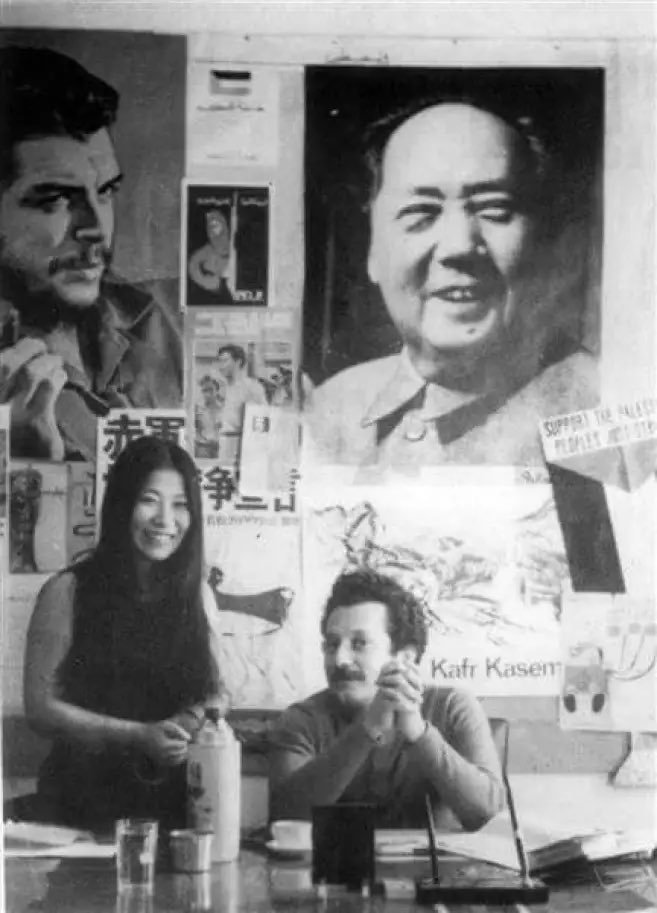

Fusako Shigenobu (L) and Ghassan Kanafani (R) at the office of al-Hadaf magazine in Lebanon, 1972. Behind them are portraits of Che Guevara and Mao Zedong as well as a poster for Sekigun-PFLP.